From silk scarves to superchips - 7 factors powering dynasties

Always ask: is this edge self-reinforcing, and does it create asymmetric pain for competitors? If it can be bought, replicated, or hired away, it’s not Power.

Many companies have unique, innovative products that succeed in the short term but are not durable over longer horizons. In this article we dive into Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework and how you can apply it to your investment ideas.

Building an Economic Moat

To succeed in the long run, great businesses must build what Warren Buffett calls an "economic moat", a term Buffett coined as an homage to the moat of a castle, that comprises one or more factors that enable a company to produce products and provide value that others cannot.

While the moat is a cornerstone of any company’s success, it is not a static target and must constantly be torn down and rebuilt as industries and the companies within them evolve. Enter Hamilton Helmer and his 7 Powers framework.

This framework differentiates momentary advantage from durable Power - concepts which are often confused.

Always ask: is this edge self-reinforcing, and does it create asymmetric pain for competitors? If it can be bought, replicated, or hired away, it’s not Power.

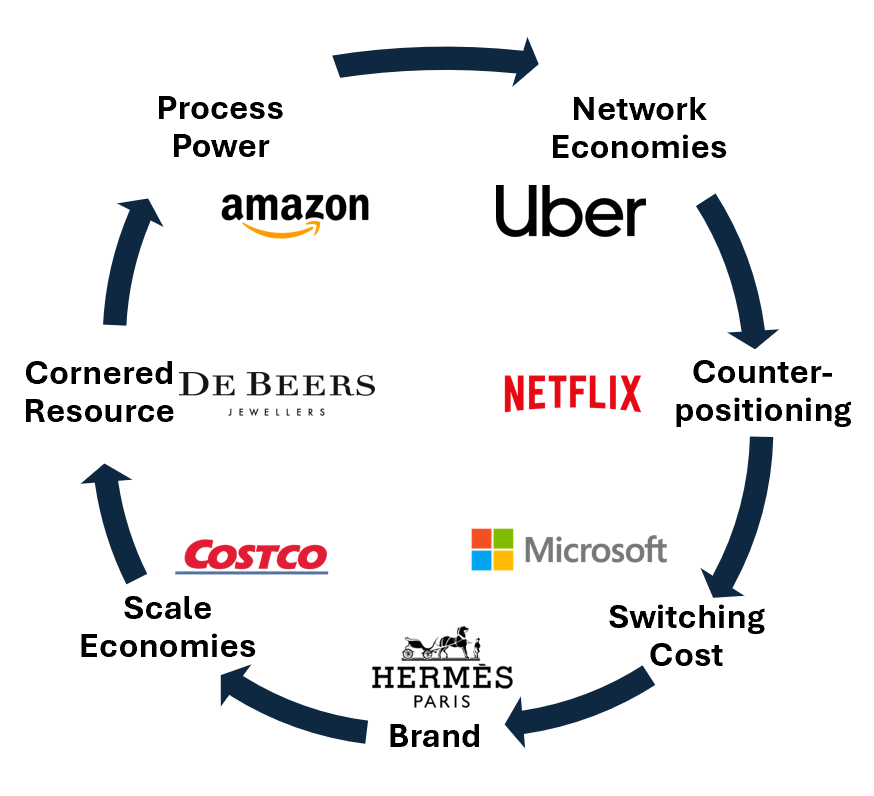

The 7 Powers framework

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers outlines 7 strategic levers (powers) that enable a company to create enduring value and defend against competition.

Here’s a quick cheat sheet, with further detail and explanation down below:

Scale economies: per-unit costs decline in a way that creates structural cost advantage as output increases.

Network economies: each additional user increases the product’s value for all other users.

Counter Positioning: the incumbent is rationally unwilling to copy the entrant's superior model because doing so would harm its existing business.

Switching Costs: Customers would face significant pain—operational, financial, or psychological—if they switched to a competitor.

Brand: Allows the company to charge a premium or retain customers without superior functionality.

Cornered Resource: Exclusively controlling a critical resource or asset (e.g. talent, IP, data) that competitors cannot replicate or acquire.

Process Power: A unique set of processes within a company that are extremely difficult to replicate and yield superior performance.

1. Scale Economies

Scale economies are cost advantages that a business gains due to its scale of operation - e.g. per-unit costs decline in a way that creates structural cost advantage as output increases.

These typically occur in one of three ways:

Purchasing power: Companies like Costco, which orders large quantities of few products, often account for the majority of their customers’ business. Due to this, they have significant bargaining power that can drive lower costs.

Efficiency gains: As a company grows, efficiency can be gained in many ways, including greater skill in producing goods or gains from methods or machinery that can be employed only at higher volumes.

Fixed-cost amortisation: New competitors face the substantial barrier of investing hundreds of millions or billions in production, research, development, or marketing. Companies like Nike can invest in large sponsorship deals that competitors can’t afford because it can spread the cost over its massive customer base. This, in turn, attracts more customers and creates a virtuous cycle.

Key Indicators: Marginal cost advantage is durable and compounds with growth. Competitors can’t match pricing profitably at smaller scale. Evident in infrastructure-heavy businesses (e.g. TSMC, AWS).

False Signals / Illusions: Temporary margin improvement via fixed cost leverage. Marketing scale or brand spend without structural cost advantage.

2. Network Economies

Network economies occur when the value of a product or service increases as more people use it e.g. each additional user increases the product’s value for all other users. When a firm truly wields Scale Power, each incremental unit becomes cheaper to produce in a way rivals cannot replicate, creating a runaway cost advantage.

This can be broken down into direct and indirect effects:

Direct network effects: Value increases directly with the number of users. For example, Uber's value increases when more people use it because this drives an increase in drivers, greater area coverage, and more reliable pick-up times.

Indirect network effects: Value increases due to the growth of a complementary network, such as content or service providers. An example is the popularity of Apple’s iOS platform, which attracts developers to create apps for iPhones, making iPhones more attractive to consumers. The more users the platform has, the more developers are incentivised to create applications for it, etc.

Key Indicators: Churn rises if network density declines. User retention or conversion improves with user base growth. Strong network utility (e.g. liquidity, communication, reputation).

False Signals / Illusions: Large user base with siloed interactions (e.g. forums, individual communities). “Community” claims without user interdependence.

3. Counter-positioning

Counter-positioning occurs when a company adopts a superior business model that competitors are unwilling or unable to adopt e.g. the incumbent is rationally unwilling to copy the entrant's superior model because doing so would harm its existing business

An example of this was Netflix's disruption of the distribution model for movies and TV in the early 2000s:

Netflix introduced a subscription model with unlimited rentals for a flat monthly fee, eliminating late fees and offering customers more predictable costs.

Traditional video rental companies like Blockbuster had significant investments in physical stores and inventory, making it difficult to pivot to an online model without incurring substantial losses.

The shift from per-rental fees to a subscription model also threatened incumbents' existing revenue streams, creating further disincentive to change.

Key Indicators: 1. New model is superior and economically threatening to incumbent. 2. Incumbent inaction is rational, not incompetence. 3. Look for cannibalization risk, internal conflict, or shareholder resistance.

False Signals / Illusions: Legacy players just being slow or bureaucratic or entrant’s success driven by novelty, not business model asymmetry.

4. Switching Costs

Switching costs refer to the monetary, time, or psychological barriers that dissuade customers from purchasing a competing product. Would customers face significant pain—operational, financial, or psychological—if they switched to a competitor?

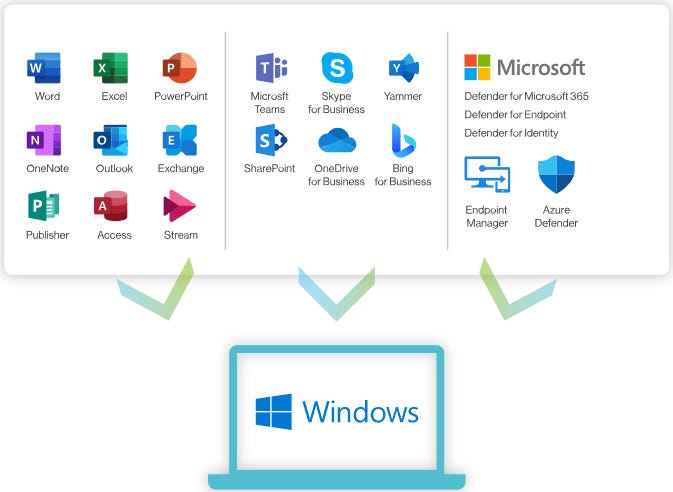

While there are many types of switching costs, they aren’t all created equal. The best types are those that are entwined the deepest in user behaviour, with ecosystems of multiple products and integrations that are hard to replace as a collective.

Some types of switching costs include:

Ecosystems: When a product or service is part of an ecosystem, switching costs increase due to dependencies on related products or services and the impact of bundling. Because Microsoft bundles its products into a single cost line and makes integration between its apps seamless, this creates a high hurdle for competing products to overcome.

Integrations: When a product or service is integrated into a customer’s workflow or system, switching can require reconfiguring or replacing complementary products.

Product complexity: Customers invest time and effort in learning how to use a product or service. The more complex the product, the steeper the learning curve and the higher the switching costs.

Psychological: In products like social media platforms, there may be a psychological barrier to switching unless the rest of your network also switches.

Key Indicators: Customer retention is non-contractual and irrationally sticky. Migration requires retraining, data transfer, or workflow disruption. High multi-year NRR (Net Revenue Retention).

False Signals / Illusions: Habit or laziness misread as lock-in. “Sticky” product with low actual friction to switch.

5. Brand

Brand power is defined as a company's ability to create a perception of greater value e.g. it allows the company to charge a premium or retain customers without superior functionality.

Some examples of brand power at work include:

Value signalling: Brands often use their products to signal certain values to their customers, such as luxury, sustainability, or innovation. Consumers then adopt these products as a way to communicate their own values and identity to others. For example, owning a Hermès Birkin bag shows others you are part of an exclusive community that both has the means to acquire a bag and appreciates the quality and heritage of the brand.

Perceptual adaptation: People become accustomed to products over time, developing a specific expectation for the taste and feel of their preferred brand (think Coke vs. Pepsi). Once they are adapted to this specific sensory experience, any small change from it becomes noticeable and often distasteful.

Key Indicators: Customers pay more despite viable alternatives. Brand signals identity, trust, or status—not just familiarity. Pricing power sustained over time.

False Signals / Illusions: Marketing spend confused with brand Power. High awareness without pricing premium or loyalty.

6. Cornered Resource

Cornered Resource stems from exclusively controlling a critical resource or asset (e.g. talent, IP, data) that competitors cannot replicate or acquire. This could be proprietary technology, exclusive partnerships, high-quality people, or regulatory licenses.

Technology: Companies like TSMC and ASML have developed bleeding-edge technologies and have proprietary knowledge that competitors cannot replicate without spending years and billions of dollars on R&D.

Partnerships: Strategic alliances, like Apple's exclusive agreements with key suppliers, enable companies to secure priority access to the best components and technologies. This leaves competitors with inferior options or longer lead times.

People: Quality staff are scarce, particularly in highly technical or specialised fields. Hermès, for example, employs the majority of the world’s artisan leather goods makers.

Intellectual property: Pharmaceutical companies like Eli Lilly rely heavily on patents to protect their drug discoveries, with exclusive rights to produce and sell a drug for a specified period.

Raw materials: Control over raw materials can create barriers for competitors who struggle to secure the same quality or quantity of resources, leading to higher costs or limited production capacity. De Beers, for example, has historically dominated the diamond industry by controlling a large portion of the world's diamond supply.

Key Indicators: The resource materially improves competitive position. It’s truly exclusive—contractual, legal, or deeply embedded. Examples: proprietary data, founder credibility, exclusive supply rights

False Signals / Illusions: Generic talent or public data miscast as “cornered.” Superstar founder effect exaggerated or commoditized over time.

7. Process Power

Process power refers to the superior execution of business processes that drive efficiency, quality, or innovation. Companies with strong process power have developed a unique set of processes that are extremely difficult to replicate and yield superior performance.

Process improvement: Amazon's ethos is centred around constant improvement. The company uses data and customer feedback to continually improve its processes, from supply chain to customer experience.

"Our success at Amazon is a function of how many experiments we do per year, per month, per week, per day. Being wrong might hurt you a bit, but being slow will kill you." - Jeff Bezos

Process innovation: NVIDIA has historically outpaced its competitors by pioneering more efficient processes, like virtual simulations and AI-driven design, allowing it to achieve faster product development timelines than its competitors.

Key Indicators: Tacit knowledge embedded in workflows and culture. Long-term consistency in execution excellence. Competitors fail to match outcomes even after copying inputs.

False Signals / Illusions: “Good culture” or operational excellence without hard-to-copy process depth. High performance explained by temporary leadership, not systems.